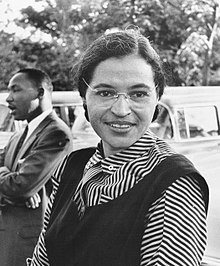

Civil Rights leader Rosa Parks’ birthday is coming up Feb. 4, so it’s a great time to celebrate the life of this extraordinary and brave woman. In December 1955, at the age of 42, she made one of the most courageous and significant decisions in the civil rights movement.

After a day at work, Parks boarded a Montgomery, Alabama, city bus for home. She sat near the middle of the bus behind 10 seats that were reserved for white people. However, as the bus began to fill, and the 10 reserved seats were taken, a white man got on the bus. Parks and three other African American passengers were told by the driver to give up their seats.

Parks refused, and in doing so, helped change the course of history. She was arrested and four days later convicted of violating a city ordinance. She paid a $10 fine and court fees.

Bus boycott

African American leaders including E.D. Nixon, Martin Luther King, Jr. and members of the Women’s Political Council organized a boycott of the Montgomery bus system for the day of Parks’ trial. On that day, the WPC distributed the 35,000 leaflets that stated:

distributed the 35,000 leaflets that stated:

“We are…asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial … You can afford to stay out of school for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don’t ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off the buses Monday.”

Some black community members rode in carpools or traveled in black-operated cabs that charged the same fare as the bus, which was 10 cents. However, most of them walked.

The boycott continued for more than a year and because African Americans comprised 75% of the Montgomery ridership, it was an economic problem for the city. Many of the buses remained parked until the U. S. Supreme Court repealed the segregation law in December 1956.

Parks’ story is the best known, but she was not the first to resist the law. Several other brave women led the way. To name a few, in early 1942, Bayard Rustin refused to give up her seat. Irene Morgan did it in 1946 and in 1951, Willie Mae Bradford resisted the law.

In Parks’ autobiography, My Story, she said that some accounts of her refusal to give up her seat on the bus indicated that she refused to give up her seat because she was tired after a day’s work.

Tired of giving in

“No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in,” she said.

She had been bullied by white children as a child and was reminded every day of the differences in the way Black people were treated. Parks had to walk to school as there was no bus for Black children, but every day, she would watch the bus for the white students pass her by.

“To me, that was a way of life; we had no choice but to accept what was the custom. The bus was among the first ways I realized there was a bla ck world and a white world,” Parks wrote in her autobiography.

ck world and a white world,” Parks wrote in her autobiography.

She often fought back when she was bullied because she could “never think in terms of accepting physical abuse without some sort of retaliation if possible.”

In 1957 Parks and her husband Ray moved to Virginia and later to Detroit. She remained active in the civil rights movement and fought for fair housing opportunities for African American people. The loss of several loved ones in the 1970s resulted in less involvement in the movement.

Parks became an administrative aide in the Detroit office of congressman John Conyers Jr. in 1965, a post she held until her retirement.

Her husband died in 1977 and she moved into a retirement apartment with her mother and cared for her until her death in 1979.

Parks died Oct. 24, 2005, in Detroit at the age of 92. She was the first woman to lie in honor in the Capitol Rotunda. Parks also lay in repose in Michigan at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History.

Awards/Recognitions

She received a long list of awards and recognitions. A few include: buildings and streets, government centers and cultural centers being named in her honor; she was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame in 1983; she received the Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women; in 2006, the Super Bowl was dedicated to her and Coretta Scott King, the wife of Martin Luther King. Jr.

In addition, Parks also received the NAACP’s Springarm Medal, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and Congressional Gold Medal. Her statue is in the capitol’s National Statuary Hall.

Sources: http://www.biography.com/people/rosa-parks-9433715 and https://www.thehenryford.org/exhibits/rosaparks/story.asp